- In what started as a frantic response adverse climatic condition is now a long-term remedy to cope with recurring drought, that holds heath and people’s livelihood.

When 78-year-old Richard Cheptoo migrated from Elgeyo Marakwet four decades ago, to settle in Nakuru county, the weather was favorable with adequate predictable rainfall, a perfect match to his farming venture.

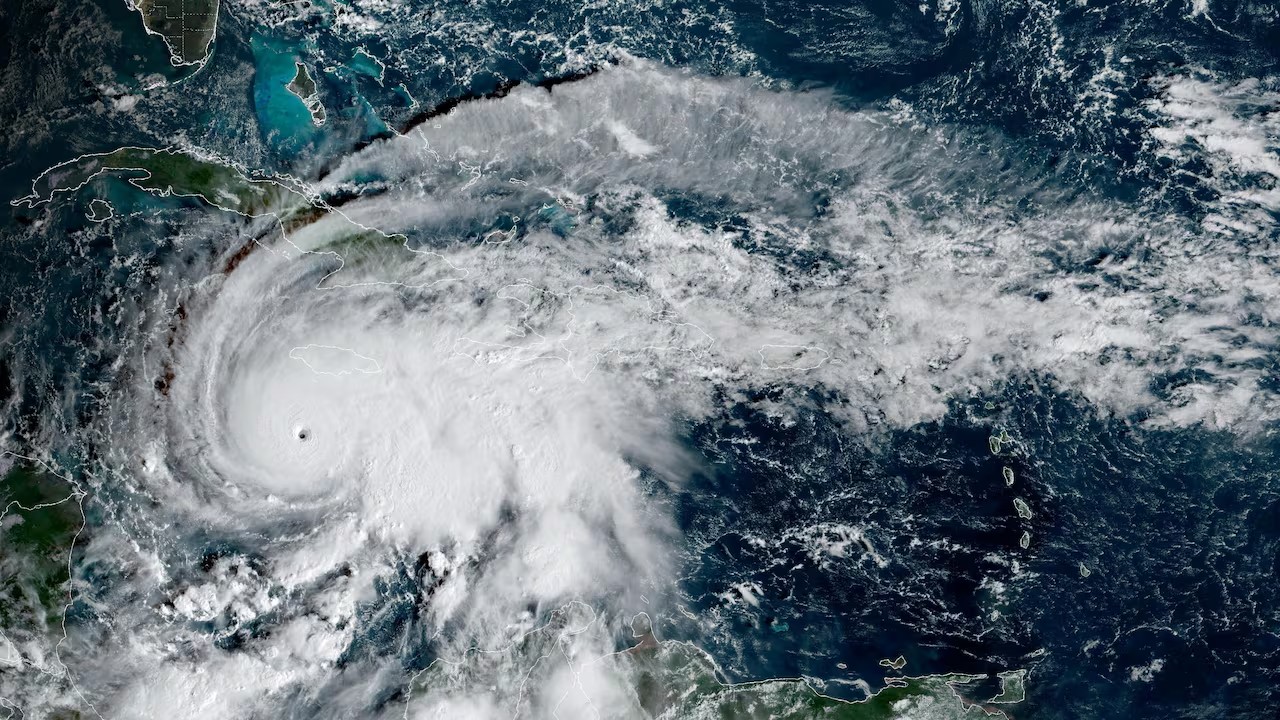

However, his comfort was not until early 1980’s where Cheptoo says he began noticing erratic rainfall patterns, with strange whirl winds strong enough to uproot planted crops.

“The worst was in 1984, I remember that year alone I planted seven times every time there was a sign of rain but lost all,” he recalls.

Read More

From then, things kept getting worse for him and other farmers who were growing white maize in Magare village of Nakuru county. Each season they lost crops to severe drought. Personally, Cheptoo says he realized that something was totally wrong when he planted seven times that year but nothing sprouted.

Cheptoo’s undying spirit kept pushing him to try again but every year was loss after another until 1990 when he had had enough, and decided to change crops. He replaced white maize with millet and Sorghum for a change.

“I started planting climate-resilient crops in 1990 when I was fed up with losing crops all the time, and they did very well,” he says.

He says though he had planted a small portion of land fearing that they might dry up like white maize, they withstood drought and he had a good harvest that prompted him to increase the portion, and added ground nuts in his 7-acre farm and since then he has never stopped.

Mzee Cheptoo says these indigenous crops hold a very significant part in his culture because, no event in his community is ever complete without porridge made of Millet and Sorghum. It is also good for mothers who are recovering from childbirth.

“You know these foods are very healthy, even in our community when a mother has given birth, they cook this for her and add some honey,” he explains.

He credits additional knowledge to Seed Savers Network a pioneering organization dedicated to preserving agricultural biodiversity and empowering farming communities across Kenya, that helped him and other farmers how to grow climate resilient indigenous crops, and the art of seed saving.

Cheptoo’s income from Millet and Sorghum has helped him raise and educate his children who are now grownups with families, and have also embraced climate smart farming.

“Were it not for embracing these crops that withstood climate change, I wouldn’t have afforded their school fees,” he reflects.

A stone throw away from Mzee Cheptoo’s home stead, is 54-year-old Joseph Ngira Olesunkuli. He is among several farmers in that area that have embraced climate smart agriculture after bearing the effects of climate change.

Olesunkuli a native of Nakuru county, born and bred in Magare village, adopted climate resilient agriculture starting with groundnuts introduced to him by Mzee Cheptoo. Ole Sunkuli grew up in the farm just like many of his peers seeing their parents surviving by tilling their farms.

“I remember vividly when I was young, my father’s store would fill with maize to the point where we had to open the top to accommodate more. Back then one acre produced 40 bags, but within no time it dropped to 15 bags, and even now it is at the lowest,” he recalls.

Climate change brought with it erratic rainfall and volent whirl wind that would uproot planted crops and leave the land totally bare. Ole Sunkuli tried to weather the situation by continuous planting depending on meteorological predictions, which he soon realized that it was not precise.

His efforts went on until 1997 when he harvested a half a sack from one acre of land, which earlier would give him 40 bags.

“The meteorologists failed terribly in their predictions. We lost a lot while planting hybrid maize depending on their predictions,” he said.

Sunkuli’s turning point too came when he met the Seed Savers Network who taught him indigenous seed selection from the main maze cob, that has been harvested directly from the farm to cut cost of buying commercial hybrids which are not climate resilient.

He has since broadened his venture into growing rare indigenous red and yellow maize.

“They taught us how to select indigenous seeds directly from our harvest. These have a 100 percent germination rate and can withstand climate adversities,” he said.

He now expects a minimum of 14 bags from a half an acre of the red maize that is already drying in his farm, far much higher compared to white maize grown on the same size that produces between 9 to 11 bags.

“Since we have moved from growing hybrid seeds to indigenous ones now, we are free farmers," he says.

Sunkuli says that the demand of the red and yellow maize too high for farmers to meet. With high market demand — red maize sells at Ksh 8,000 per 90kg bag compared to Ksh 1,800 for white maize — indigenous crops are not only restoring food security but also sustaining livelihoods.

According to Dancan Mrabu a climate change expert in Nakuru, Cheptoo and Sunkuli’s decision to adopt and grow yellow and red maize is a sign of a rising recognition of the value of indigenous crops in a changing climate.

This indigenous variety of seeds have been known to withstand harsh weather conditions and pest resistance, and can also do well in poor soils, compared to the hybrid varieties.

“Yellow and red maize variety are naturally adapted to different environments and weather conditions making it preferable for climate resilience,” Dancan says.

As ravages of climate change continue being felt across Kenya and threating food systems, farmers like Cheptoo and Sunkuli are a true testimony of how beat the effects of climate change by planting climate resilient crops leading to survival and prosperity of people.

In what started as a frantic response adverse climatic condition is now a long-term remedy to cope with recurring drought, that holds health and people’s livelihood.